My collective, consensus-based approach to creativity means that this space, too, must reflect a collective.

So here goes:

In collaboration with Michael Hart—whom my amazing (but sadly estranged) cousin, Treva Wurmfeld, introduced me to back in the late oughts—this site has been born.

Here, you’ll find a digital homage to the places, people, and creative communities that shape my life and work—as a director, musician, parent, and neighborhood organizer.

Photo: André Breton’s beetle collection, an object-based convergence of natural specimens and ethnographic artifacts—courtesy Association Atelier André Breton.

This space brings together the projects and people who inspire me every day. Root around, be inspired, and consider yourself invited to share in the collective creativity and joy that connect me to all of it.

Photo: Installation, Vermont, 1996 by Hope Herman Wurmfeld.

After eight years of near-total immersion in parenting (with some music-making on the side), I’m re-engaging—opening myself to new personal projects, scripts, and collaborators.

Photo: Stella H., adopted in 2020; Hope H., adopted in 1934.

If you're interested in collaborating or connecting, reach out and let’s build something beautiful together.

Love,

Charlie

Summer 2025

photo: The North Rose Window of Chartres Cathedral in France.

HOMAGE | HOPE HERMAN WURMFELD

No one can truly claim to be anywhere or anyone without acknowledging the undeniable truth of a mother.

HOMAGE | HOPE HERMAN WURMFELD | PART I

The Legacy of Hope Herman Wurmfeld: An (ongoing!) Life of Art, Photography, and Reflection on Death

No one can truly claim to be anywhere or anyone without acknowledging the undeniable truth of a mother.

And I got:

Hope Herman Wurmfeld, a 90-something photographer, educator, and fearless chronicler of life and death, still lives and works in New York City. Her life is a study in creative attention—rigorous, unsentimental, and luminous. Her medium has always been light.

Fitting, then, that her first spoken word was “light.”

Hope was born in the Bronx and raised on Packman Avenue, in a home shared with her mother, grandmother, and extended family. Her grandmother, who spoke only Yiddish and kept kosher, ruled the kitchen with an iron ladle and swore she didn’t like the family dog, Sadsack—whom she called “Fartsick”—but secretly fed him scraps and cooed to him when no one was looking. From her Grandma, Hope absorbed the sound and cadence of Yiddish, even if she never took to religion itself and quickly assimilated the King’s English. Hope—though quick to Google—remains, proudly and defiantly, a 20th-century person—skeptical of all things spiritual, but even still attuned to the mysteries of life in spite of herself.

Hope’s father, Charlie Herman, was a visionary storyteller, comic book artist, and illustrator—a contemporary of Walt Kelly, and a man whose career never quite took off. He was funny, kind, wildly imaginative, and beloved by Hope. One of his stories, The Wedding Cake Pastry Dolls, has lived on in our family lore—tiny sugar figurines who come to life and set off on a dangerous journey through the city to find the Island of Pastry Cakes, dodging rain, rats, and a vengeful baker along the way. I’ve told it to my kids many a night, and still hope to bring it to the screen.

When Hope’s first husband, Bob Ellis—her high school sweetheart—died in the 1960 Park Slope air disaster, she was in her twenties. Grief cracked the timeline of her life, but she didn’t stay still for long. Instead (with the blessings and encouragement of Bob’s Mother, Esta Ellis), she took herself to Fontainebleau, France, where she enrolled in a painting course and had a summer of art and tentative romance. It was there she met my father, who arrived with a bandaged head from wrecking his Vespa. She thought he looked dashing. When a group of students made a halfhearted plan to go to the running of the bulls in Pamplona, only Hope and my dad actually showed up at the train platform. They talked the entire ride, fell into something that felt right, and were inseparable not long after.

Genoa, Italy, 1964, © Hope Herman-Wurmfeld

photo: Porta Portese, Rome. Courtesy of © Hope Herman Wurmfeld

HOMAGE | HOPE HERMAN WURMFELD | PART II

Hope went on to discover photography; documenting her neighborhood of Trastevere (pronounced trash-TEHveh-ray, a word meaning “across the Tiber”). There she and my dad lived in a glamorous little walk-up apartment with a terrace overlooking the city. There she first noticed women in black (mourning, after the war) and connected with their style and sentiment; there she adopted her signature clothing color: black. Her doctoral thesis on 19th-century post-mortem photography, and death—as subject, metaphor, and mystery—has animated her work ever since. She sang us death ballads in our childhood: Tom Dooley, The Streets of Laredo, Clementine, Dublin’s Fair City, Ride an Old Paint. Her voice (and guitar styling) tentative, but persistent, and the songs laid a strange and steady foundation for the kinds of stories, songs, and pictures that now draw my attention—those where grief and joy ride tandem.

She taught me how to see. In the basement darkroom of our childhood home, she showed me how to work with light, the quiet, the chemical magic of the image emerging in silence. Her hands working steadily over the trays of chemical and water were my first experience of precision and creativity. That’s where I learned: Art is time. Art is ritual. Art is light. Art is devotion.

Her early photography captured black-and-white portraits of Italy, Russia, and France in the 1960s. Later came the haunting brilliance of Dream Garage, a rephotographed photo-sculpture series staged in garbage dumps—meditations on decay, aging, and the myth of permanence. She documented many women who came to sit for her Mothers & Daughters Series, including the life and work of her lifelong friend/sister/cousin Joyce Aaron. This work effectively chronicled the New York theater avant-garde through Joyce’s work in The Open Theater, La MaMa, and Lincoln Center.

For over two decades, Hope taught photography at Hunter College, where she passed along not just skills but vision. Her work has been exhibited across the U.S. and internationally, and is housed in permanent collections at the Museum of Modern Art and the Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

She also made indelible portraits of our chosen community in Goshen, Vermont, where she and my dad restored an 18th-century farmhouse in 1971. Goshen, newly accessible year-round after Route 73 was cut through the mountains only a decade before, was a place where neighbors still relied on each other through the long, cold winter. Her photographs from that era—portraits made in the barn, candids on porches and at swim lessons—are intimate, clear-eyed, and filled with grace. There we encountered and learned from people who were so very different from the New York City creatures we were upon arrival. There our whole family learned how to be good neighbors. And our neighbors learned which was the bagel and which was the lox.

Aosta, Italy, 1964 | © Hope Herman-Wurmfeld

HOMAGE | HOPE HERMAN WURMFELD | PART III

And yet even as we were learning the codes of neighborliness in Vermont, there was another language I hadn’t yet learned to speak—one that lived in the silence between me and my family. I didn’t yet understand myself as a gay person, and for a long time, no one (except the taunting children at school) seemed to see it either. But I believe my mother did. Not in the way people sometimes claim after the fact, but in the way she listened, the way she made space without pushing. She was embracing me in my queerness before any of us had the words. I think she sensed the shape of who I was before I did, even when it meant coming into conflict with my father, who took longer to understand. Through those late ’70s and early ’80s years—through adolescence, confusion, the messy process of trying to become—she showed up, camera in hand, making room.

I remember, during the making of Kissing Jessica Stein, Hope not only served as the on-set photographer, but generously offered up our family home as a base of operations (casting office, production office and hot set)—just weeks after my father had died. We hosted auditions in the front room of her brownstone—my sister’s bedroom turned casting office. I remember the day we auditioned actors for the role of “Jessica’s Dad.” It was surreal, hilarious, and strangely sacred. Hope, as always, held the space in her madcap way.

She still tells me she’s “coming along” when I speak of travel or sabbaticals. She’s still planning to learn to speak Italian. She’s still orchestrating and unveiling the millions of photos she’s taken over a lifetime. And I believe her. She’s been coming along my whole life—in voice, in image, in example.

Hope is not sentimental. But she is quietly fierce. Trickily honest. Luminous. A woman who mistrusts religion but holds reverence for process, form, and truth. She’s taught me to see clearly, love deeply, and stay true.

Thank you, Mama. For the darkroom. The death ballads. The fearless seeing.

You gave me the light.

HOMAGE | MICHAEL WURMFELD

Architect, Artist, Educator, Father

HOMAGE: MICHAEL WURMFELD | PART I

Michael Wurmfeld (1939–2000) lived by his values. He believed in fairness. In precision. In generosity. In making room—for neighbors, for students, for the people he loved. He was brilliant, principled, often difficult, and deeply loved.

He could be intimidating. People were sometimes afraid of him. He had piercing blue eyes, a sharp intellect, and movie-star looks. He was intense. Commanding. He cared deeply about the work, but never quite knew how to advocate for himself without ambivalence. That tension shaped much of his career.

He was raised in a time when men were expected to be strong & stoic—he was shaped by 20th-century masculinity. He didn’t talk about feelings easily. And yet, he showed love in ways that were unmistakable. Through structure. Through care. Through presence.

Each spring in Murray Hill, he would plant pansies on our front stoop. One tray for our building, another for the neighbors. A quiet act of beauty. He wasn’t a gardener by nature, but he showed up, soil on his hands, trying to make something nice for someone else.

His generosity was large, and often surprising. Long before my mother found her biological family, he invested himself in her search—deeply. I remember landing at the Las Vegas airport on a family trip out west, where they kept stacks of phone books from around the country. We spent hours flipping through them, scanning every page for the name Scalzi, hoping to trace a line back to the people she came from.

HOMAGE: MICHAEL WURMFELD | PART II

When that search bore fruit in the 1980s, and long-lost family members from her biological side began to emerge—cops, firemen, Italians from Long Island and overseas—my father was at the front of the line to welcome them. One cousin, Mauricio Scalzi, came from Italy with dreams of becoming an architect. My father gave him a place to work in his office and a place to sleep in the basement. That’s the kind of thing he did—not because it was expected, but because he believed it was right.

In 1972, he voted for Shirley Chisholm, the first Black person to seek a major party nomination for president. He supported progressive candidates consistently. He believed in equity, public institutions, civic responsibility, and in lifting up others—not for attention, but because it was the right thing to do.

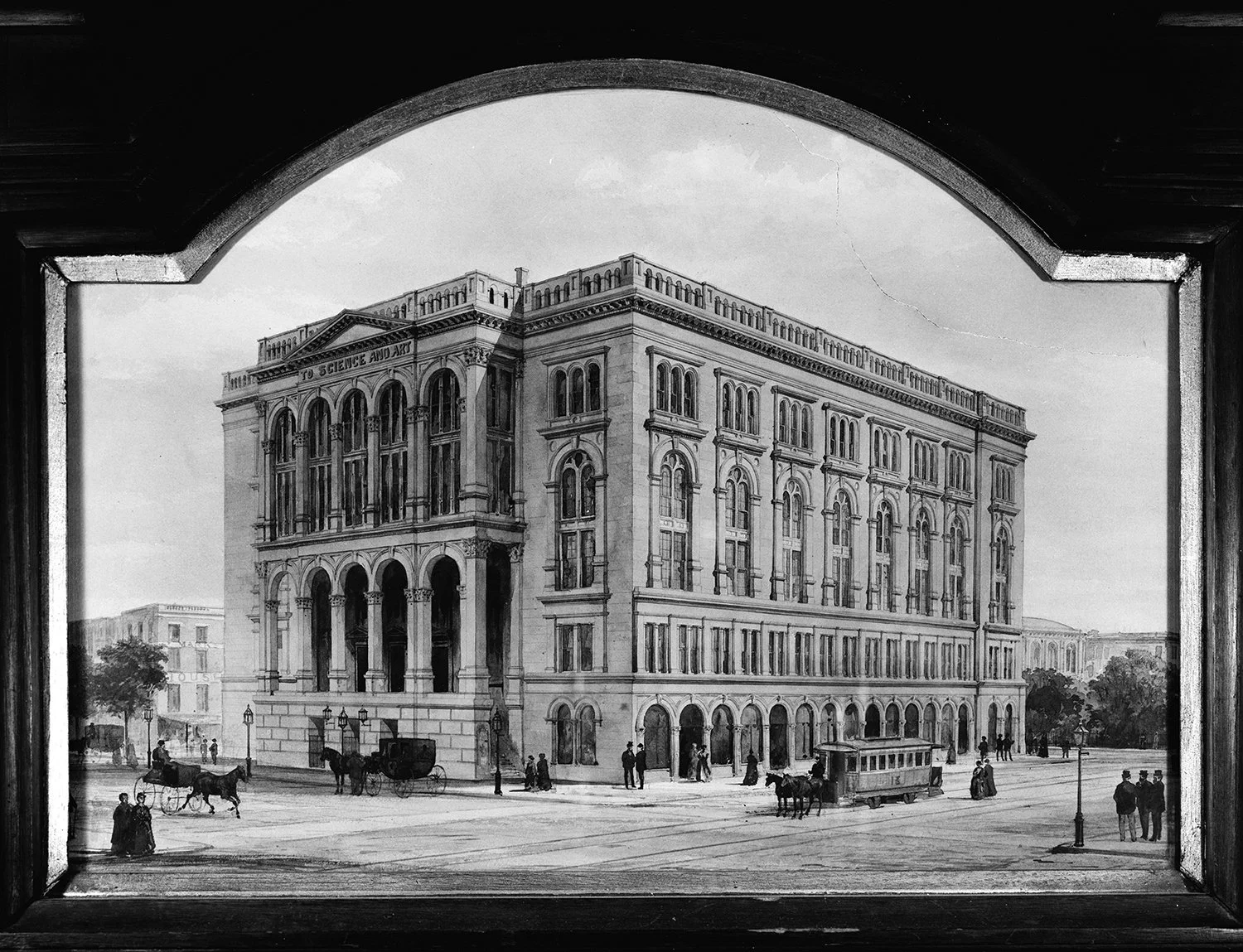

He taught architecture at Cooper Union in the 1970s, where his hand-drawn renderings—in pen, pastel, graphite—were celebrated and exhibited. His students remember him for his vision, his standards, and his stubborn refusal to follow architectural fashion. While postmodernism surged, my dad stood his ground.

He also stood up for his fellow faculty. When the adjuncts at Cooper Union were being undercut, he tried to organize a union. He clashed with the administration, and eventually resigned. I was young, filming the teacher strike with my Super 8 camera, not knowing then that I was documenting what it meant to live your values, even when it cost you something.

He had a lifelong creative partnership with his brother, Sanford Wurmfeld, a color theorist and painter. They made experimental films together—early explorations of light, color, and structure. Their collaboration was foundational for me. It gave me a template for how siblings might co-create. It became the root system for my work with my sister, Eden.

HOMAGE: MICHAEL WURMFELD | PART III

He taught me how to see. How to notice form, frame, light, shadow, negative space. And also, how not to fall on your sword. (That part I learned by watching.)

He wasn’t an easy dad. I remember him trying to teach me basketball when I was four. I didn’t get it, and he didn’t get why I didn’t get it. We both left the court frustrated. I swore I’d never play again. (Decades later, with Jason’s dad, I discovered I actually might love basketball after all.)

When I came out to him, it was hard—for both of us. He struggled, and he tried. Later, when I brought home Jason, something softened. Maybe he saw a version of himself in him—smart, driven, more conventional than I was. We used to joke that he liked Jason more than me. But he really did love him. He loved the people I loved. That mattered.

He didn’t get to see my career take off. Mysteriously, it was immediately after he died that things started to move. But he did hear a stage reading of Kissing Jessica Stein, and I remember how much he enjoyed it. He had a glimmer, at least, of what was coming.

His death from preventable colon cancer was a terrible loss. If you’re over 50: please get screened. It saves lives.

The last thing he said to me was, “Call me. We need to talk.”

I wish we had talked more. I wish there had been more time. But I carry his clarity, his contradictions, his charm. He made people feel welcome. That part lives on in me.

Thank you, Poppa. For the values. For the structure. For all of it.

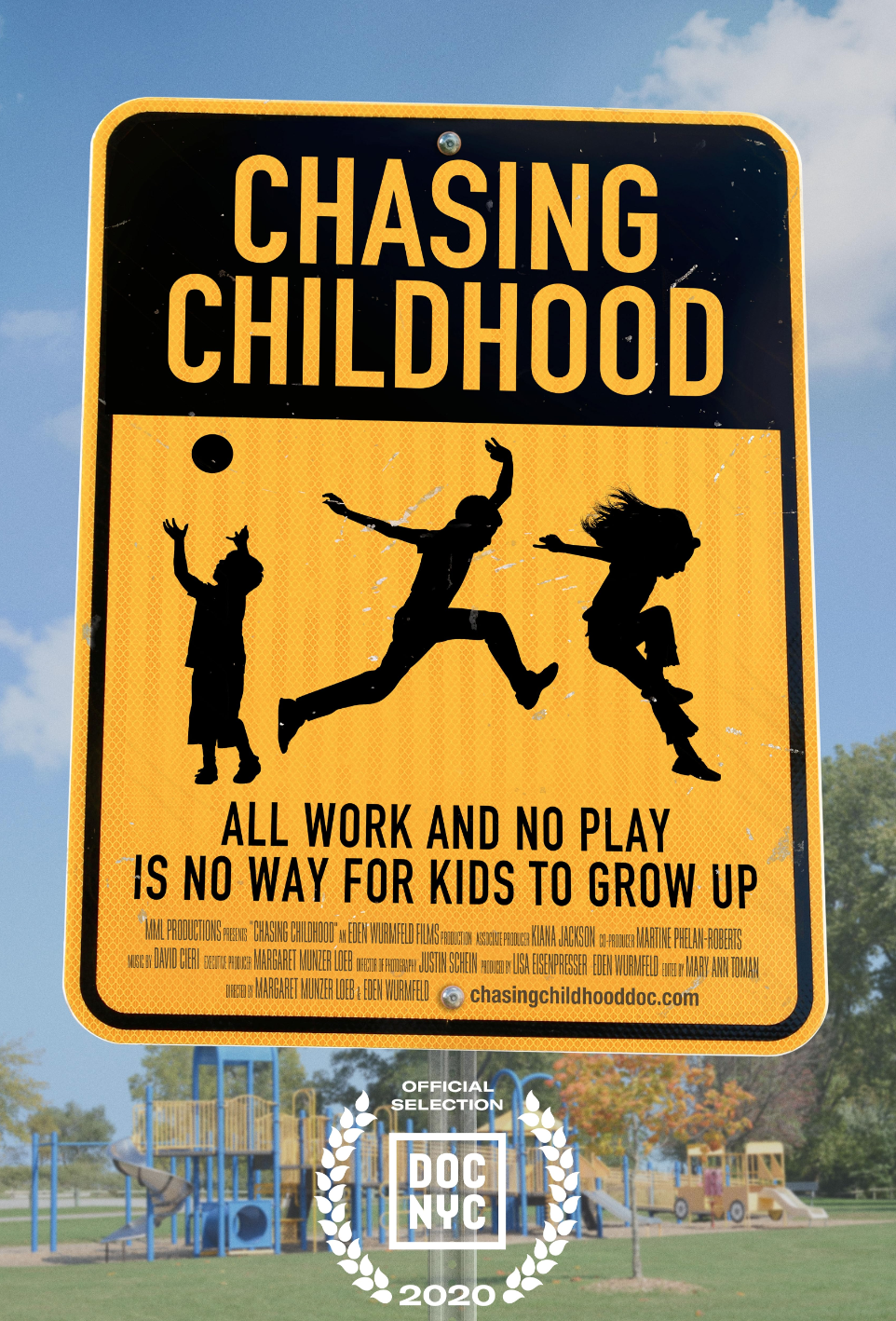

HOMAGE | EDEN H. WURMFELD

Sister. Producer. Pathfinder. Co-author of a lifelong collaboration.

HOMAGE: EDEN H. WURMFELD | PART I

Eden arrived just about half way through my third year, and to put it gently—I was skeptical. Who was this tiny, fearless creature suddenly showing up everywhere I wanted to be, claiming space like she was twice her size? But even back then, it was clear: Eden didn’t follow. She simply joined. With purpose. With presence. With power.

We grew up straddling two very different landscapes. In Murray Hill on 31st Street, the block was our playground—filled with families, shoulder-wars, bruised knees, and summer dusk. Eden took one particularly dramatic fall in one of those games and came up skinned but unbowed—tough, wide-eyed, already legendary in my mind.

In rural Vermont, we ran barefoot across pastures, swam in the pond, and rode horses—Heather and Merlin—through the woods with no agenda but wonder. We learned early how to companion each other through wild terrain, and how to let the land shape us.

We tried on a lot of schools—Horace Mann, Friends Seminary, Fieldston, Oberlin—a patchwork journey toward voice and belonging. Somewhere between the cafeterias and the college seminars, we discovered our power as collaborators. Our first joint act of resistance was a Students for Peace rally during the Reagan years—protesting military tourism and nuclear escalation. Eden had the organizing chops. I had the performance bug. Together, we could move a room.

HOMAGE: EDEN H. WURMFELD | PART II

That magic found its full expression in our creative work—especially on Kissing Jessica Stein, where we weren’t just making a movie. We were making meaning out of grief, family, and joy. Our father had recently passed. And into that space of mourning, we brought our real-life Grandma Esther, cast as Jessica’s grandmother—a dream come true. She was in her 80s, luminous, hilarious, and, suddenly, a movie star.

We watched audiences across the world laugh at her timing. We gave her that moment, and it gave us something back we didn’t know we needed. The film was full of our actual DNA—our family home, our Uncle Sandy’s loft, his architecture department office at Hunter College—each repurposed into set pieces, into memory made visible.

Eden produced that project the way she does everything: with rigor, elegance, and deep intuition. She’s not a joke-cracker, but she’s one of the people who makes me laugh the hardest—because she sees the world clearly and doesn’t look away.

Since the ’90s, we’ve also shared a yoga practice—born out of fits of laughter in impossible poses at YogaWorks in Santa Monica, under the guidance of Chuck and Maty. It became more than a practice. It became a shared language. A compass. A way back to each other.

photo: Hope Herman Wurmfeld. From left: Heather Juergensen, Jennifer Westfeldt, on the set of Kissing Jessica Stein (2001). Directed by Charles Herman-Wurmfeld; produced by Eden H. Wurmfeld.

HOMAGE: EDEN H. WURMFELD | PART III

Though we now live on opposite coasts, the connection remains elemental. When we can, we steal away for long walks, short retreats, deep breaths. Eden is one of the people I trust most in this world. She has always held the steady line, even when I’ve wavered.

We’ve collaborated in protest and in art, in heartbreak and in celebration. And through it all, she has been what she was even back then on the streets of 31st Street: brave, present, ready, and unmistakably right where she belongs.

SONG OF MYSELF | CHARLES HERMAN-WURMFELD

Film Director, Musician, Community Organizer, and Parent

SONG OF MYSELF: CHARLES HERMAN-WURMFELD | PART I

Hi, I’m Charles Herman-Wurmfeld—some people call me Charlie and my biggest fans go with Wurmy Wormfield (and I’ve learned to take that as a compliment). I’m a film director, musician, community organizer, and parent. But mostly I’m just a person with a sincere desire to explore what connects us and to help build a world that’s more just, joyful, and alive.

You might know me from films like Kissing Jessica Stein or Legally Blonde 2: Red, White & Blonde. Those stories gave me a chance to lean into the humor and resilience that define us, and in a big, public way. But some of my most meaningful work has taken place off-screen: organizing in my neighborhood, planting over dozens of trees across Los Angeles, helping co-found the Micheltorena Community Garden—a plotless, shared urban oasis where neighbors gather, dig, and co-create something wild and generous together.

A lifelong bicycle enthusiast, in the late 1990’s I co-founded Los Angeles Critical Mass and was part of the early movement behind the Los Angeles Bicycle Coalition—advocating for safer, greener streets long before it was a thing. And yes, I still bike the light fantastical. (Literally—I wrote a song about it.) This work really matured later on as I collaborated with neighbors to envision and then rework a local road into public space now called Polka Dot Plaza.

SONG OF MYSELF: CHARLES HERMAN-WURMFELD | PART II

Since becoming a parent in 2016, my creative focus has shifted once again. I began writing and recording children’s music, inspired by my kids and the community garden I loved. My 2022 debut album For You, the Garden is a love letter to community, to nature, and to the belief that even the youngest among us deserve an opportunity to ponder environmental stewardship and radical empathy.

I approach everything—film, music, organizing, parenting—as a collaborative practice. Creativity, for me, is rooted in relationship: with people, with land, with the rhythms of life that aren’t always linear or clean, but are always rich with meaning.

I haven’t had a straight path here. As a young person, I was full of imagination and ambition, but also deeply delayed by internalized homophobia and the pain that came with it—self-doubt, addictive and destructive patterns, especially around love and sex. But through healing work, sobriety, (lots of) therapy, and an almost accidental romance with yoga and plant medicine, I’ve found a more whole version of myself.

SONG OF MYSELF: CHARLES HERMAN-WURMFELD | PART III

These practices brought me back to a sense of god—not a man in the sky, but the animating force in nature itself. Through that lens, my partner Jason and I began to rebuild our lives. We adopted our two kids. Now our home is full of dance, soup, song, and more chaos than any indie film set could ever prepare me for.

So yes, I’ve directed films and led neighborhood council meetings. I’ve recorded psychedelic bike anthems and planted trees until my arms ached. But all of it—every frame, every lyric, every garden bed—is part of the same story. A story about showing up. About imagining a better world, and then doing the slow, hopeful/painful/joyful work of building it.

Thanks for reading—there’s more to come.

Signed,

I know I’m ridiculous, but I compost now.

Also: earnest dad with a past.

HOMAGE | JASON BUSHMAN

On Love, Longevity, and Building a Life with Jason

photo: Dadoo Jason 1980's, Odessa, Texas.

HOMAGE: JASON BUSHMAN | PART I

Jason and I met in a dance club in the spring of 1998. He was 21, I was 31, and it felt like one of those improbable fantasies that make you laugh years later—except, somehow, we stayed in it. I was immature, he was sincere, and we started dating anyway. I fell for his honesty, his intelligence, and—yes—his undeniable adorableness.

That summer, we fell in love. And now, almost three decades later, we’ve lived through nearly every version of relationship two people can. Marriage, friendship, collaboration, collapse, rebirth—check, check, check. It wasn’t always easy. Especially during that first decade, when my post-Kissing Jessica Stein career took off like a sparkler in a hurricane, and we were still trying to figure out who we were—as individuals, as a couple, as artists.

We started trying to collaborate early—bands, scripts, films—though not much came to fruition until the late 2000s. Looking back, I’m deeply grateful we stuck it out, but we’d both admit (and so would our inner circle, lovingly) that it’s unclear how or why we did. Maybe it’s because we both come from families where people stayed. Maybe we’re both too stubborn to let go. Or maybe, somewhere deep down, we knew we were headed somewhere good.

HOMAGE: JASON BUSHMAN | PART II

And we were.

As time passed, the sharp edges softened. We learned how to fight less and listen more. Yoga helped. Ganja helped. And eventually, Ayahuasca helped a lot. In fact, it was likely our shared work with plant medicine that truly opened the door to the version of our lives we now live: peaceful, purposeful, deeply co-created.

We’re co-parents to two beautiful humans—River Jack (born 2016) and Stella Hawk (born 2020), both adopted at birth. Our home is a place of music and ceremony, wild play and deep care. We share parenting, meals, song, and responsibilities. We’ve built something sacred out of all the mess and magic.

Here are a few things to know about Jason:

He is a fierce, steady ally—the kind of person you want in your corner when things get real. He’s razor-sharp, deeply grounded, and allergic to social media. He reads more than anyone I know, sings constantly, and pours himself fully into parenting and community.

HOMAGE: JASON BUSHMAN | PART III

Over the last decade, he’s become a medicine man in his own right—leading ceremonies with grace, humor, and a kind of stillness that brings people home to themselves.

We co-founded a spiritual community together, Gracia Divina. He also makes music—check out his songs [here]. And he’s an incredible filmmaker. You can watch his debut short film [here], and his feature film Hollywood, Je T’aime [here].

These days, there’s peace in our home. And that peace was earned, not inherited. Which makes it even more sacred.

HOMAGE | RICK KLEIN ("DON RICARDO", "UNCLE RICK")

A Life of Music, Community, and Becoming

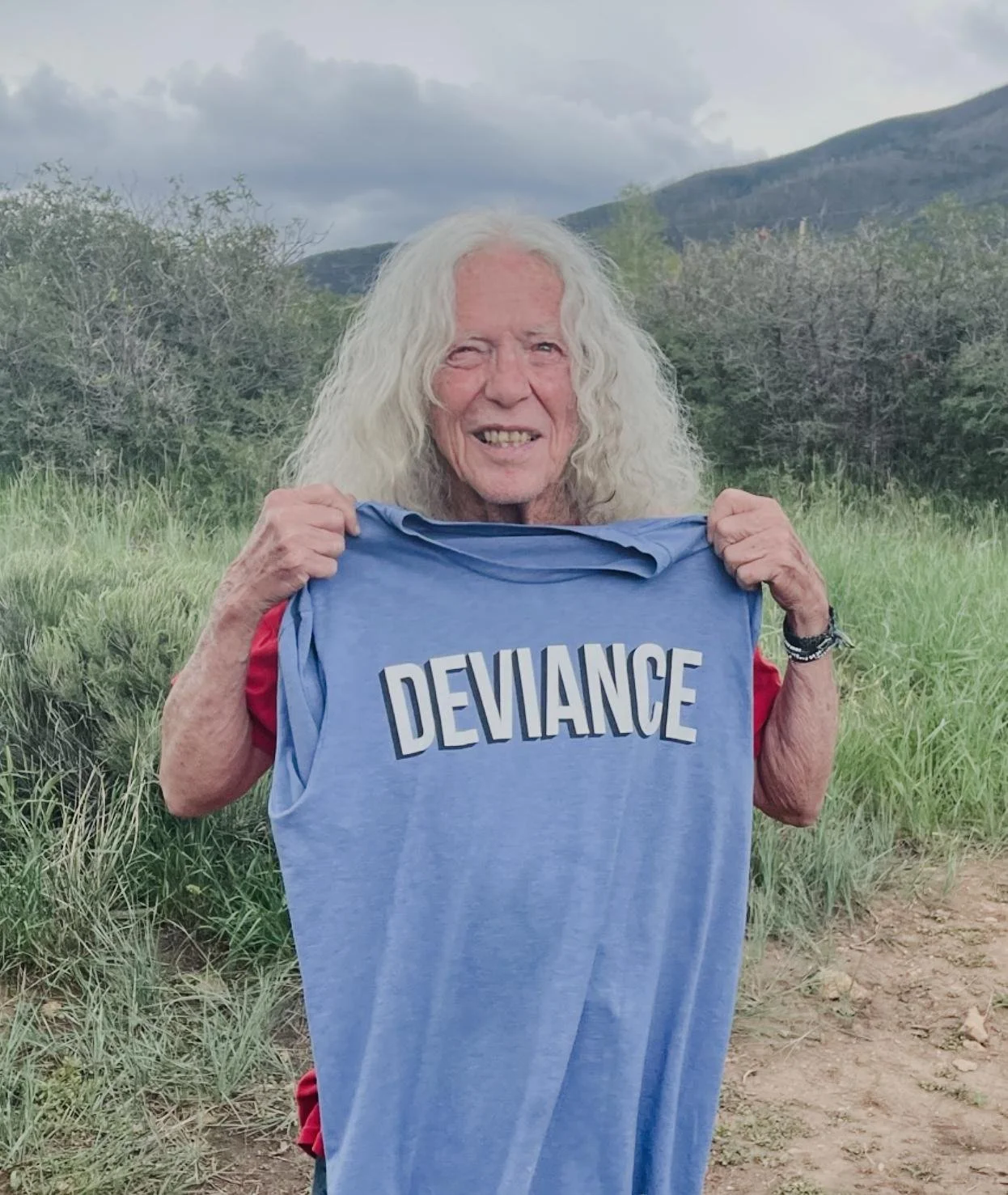

Uncle Rick Klein.

HOMAGE: RICK KLEIN | PART I

Rick Klein—Don Ricardo to some, Uncle Rick to many—walks with the kind of presence that slows time. You feel it in the way he enters a room, or sits by a fire, or raises his voice in song. He’s not a guru. Not a saint. Just a deeply human being who’s spent a lifetime practicing how to be alive.

We first crossed paths in 2009, in the roundhouse at Tony’s place, not far from Rick’s home outside Taos. From the beginning, I felt it: I’d met someone rare. Someone who had dwelled on thresholds I barely understood and had returned with stories, songs, and deep listening.

He showed me sacred photos from the Sundance at Lone Star, taken with permission, and extended an invitation. It took me a while to answer the call. But eventually, I did. Since then, I’ve been on what appears to be a ten-plus year plan to complete Vision Quest. It’s not linear. But it’s true.

I sat my first one with Jason, and others in our community—Ben, James, Matt, Jordan, Helen, and many others—made their way to the blanket outside Rick’s place. There, Rick holds the fire and leads sweat lodge, while neighbors come to cook and support and sing. That first time, we prayed for children. And they came.

In many ways, I feel like Rick helped call them in.

Uncle Rick Klein.

HOMAGE: RICK KLEIN | PART II

When we started holding ceremony in Los Angeles, Rick became part of it—organically, generously. He built relationships with our community and became a beloved elder to our children. He’s taken walks through the neighborhood (“I think Silver Lake is the most far out place on earth”), enjoyed ice cream, swilled coffee from the corner café, browsed books at Story’s Bookstore downtown. And when he comes into our house, he often says something like, “I really admire the way you guys live.” Coming from him, that lands. We do live kinda simple here, close to the floor—surrounded by green even in the sprawl of LA. That he recognizes that spirit means a lot.

He didn’t know my father—who died in 2000, years before Rick and I met—but somehow Rick’s presence fills a similar space. Not a replacement. But a continuation of something sacred and paternal, kind and unassuming.

He also—let’s be real—taught me how to play guitar. Not through formal lessons. Through jokes. Specifically, through his frequent reminders that he didn’t really like banjos.

“What happens if you leave a banjo in the back seat of your car?”

“You come back and someone’s left two more.”

He’d crack on them just enough that I got the message. I picked up the guitar. And now I play.

Rick’s roots run back to Pennsylvania—old school Pittsburgh—but his spirit cracked open in the Southwest. After college and a transformative LSD experience, he realized “there’s more to it than just this,” and used his inheritance to buy land in Taos County. In 1968, with Beat poet Max Finstein, he co-founded the New Buffalo commune. It became legendary—enough to inspire Easy Rider—but Rick wasn’t in it for fame. He was building something real.

Video: Don Ricardo - Shipibo Song.

HOMAGE: RICK KLEIN | PART III

He sought out Pueblo elders like Little Joe Gomez and spent years learning from them, always with respect, humility, and deep gratitude. That same year, Rick and his wife Terry began building their adobe home by hand at the foot of Lama Mountain. Pueblo horses helped mix the mud. Over decades, the house became a living place: children were born there, drums played on the roof, vision quests began and ended in prayer. Friends describe it as “an epicenter of ceremony.” Eventually, the walls began to crumble. Rick, now in his elder years, let go with grace: “It overjoys my heart to see the place being restored… so that it can be used from now on into future generations.”

Music is one of Rick’s oldest languages. Under the name Don Ricardo, he’s released albums like Ceremonial Songs, a collection of healing chants and spirit melodies; I also love the Black Iris Sessions (and me and Jason and others sing at the end). He’s sung cowboy tunes and Spanish folk ballads around campfires and kitchen tables. He worked for many years with Taos legend Jenny Vincent. He carries a song in his body, and when he sings, you remember something older than memory.

And he reads. Widely. Eclectically. Generously. The Don Ricardo Syllabus—a lovingly compiled catalog of his favorite books—is filled with treasures. Titles like Black Elk Speaks, Of Water and the Spirit, The Spell of the Sensuous, and Wind, Sand and Stars speak to Rick’s blend of mysticism, earth-based wisdom, and poetic attention.

Now, at 83, Rick is living in the great paradox: growing weaker and more powerful all at once. He’s begun to talk openly about death. About preparing to become an ancestor. He’s not afraid. He’s ripening. Listening more deeply. Laughing more easily. Even in stillness, there’s a fire inside him.

To be in Rick’s presence now is to glimpse what wholeness might feel like. He is a bridge between worlds—between youth and elderhood, between grief and celebration, between earth and sky. Rick Klein is a co-founder of the New Buffalo commune, a builder of homes and rituals, a singer of songs, a keeper of fire, a trickster with a twinkle. A living elder. A darling and daring friend. So grateful to call him a part of me.

Uncle Rick Klein.

💄 HOMAGE | DR. JUSTIN VIVIAN BOND

The Loving Gaze: My Friendship with Mx Justin Vivian Bond

Justin Vivian Bond, photo by Jack Pierson, 2022.

HOMAGE: DR. JUSTIN VIVIAN BOND | PART I

Among my dearest creative inspirations and lifelong collaborators is Mx Justin Vivian Bond—Viv to me—a singular force whose work spans theater, film, music, and visual art. Viv is a MacArthur “Genius”, a groundbreaking performer, a punk cabaret legend, and one of the most vital cultural voices of our time. But before all that? We were just two artists, waiting for the dream to start in San Francisco.

Back in those days—messy, magic, full of longing—we made a vow: we’d break into the world arm in arm. And for a time, we did exactly that. We performed, plotted, schemed, and laughed ourselves into the future. Our creative connection was like a secret thread made of glitter and heartbreak. It gave shape to some of my earliest and most formative artistic experiences.

Though our paths don’t cross often these days, Viv will always be part of my creative heart.

Justin Vivian Bond - American Wedding (From the album, Dendrophile)

HOMAGE: DR. JUSTIN VIVIAN BOND | PART II

Over the years, Vivian’s career has shimmered with brilliance: Broadway and Off-Broadway performances, shows at Carnegie Hall and the Sydney Opera House, unforgettable turns in Shortbus, Can You Ever Forgive Me?, and my first feature, Fanci’s Persuasion. Their presence lights up screens, stages, and rooms with equal force. And in the world of visual art, their exhibitions have graced galleries and museums across the globe.

Viv’s memoir, Tango: My Childhood Backwards and in High Heels, won the Lambda Literary Award for Transgender Nonfiction, and their musical works—like Dendrophile and their iconic performances as part of Kiki & Herb—continue to defy genre and expectation.

Viv has been a fierce and unwavering voice in trans activism since the moment I met them in 1989. They hold a Master’s in Live Art from Central Saint Martins in London, and currently split their time between New York City and the Hudson Valley. If you don’t yet know Viv’s work—do yourself a favor and dive in. It’s not a show—it’s a portal.

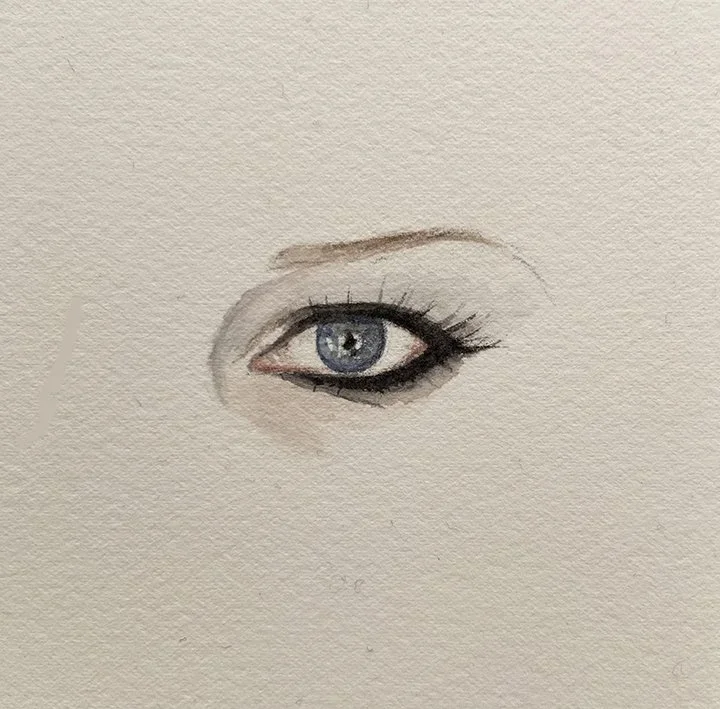

Justin Vivian Bond, watercolor on paper, 4 x 4, 2020, from the series Witch Eyes, by Viv, to protect you from evil chodes, click here to learn more.

HOMAGE: DR. JUSTIN VIVIAN BOND | PART III

Every now and then, we still find each other in the summertime, somewhere in New England, and it’s like no time has passed. We love to play cards in matching day dresses and laugh.

Here’s a homespun video from the early days: a little show called Dixie Macall’s Patterns for Living, which Viv and Kenny put on at Athens By Night, a small Greek bar in the Mission District of San Francisco, where we all lived then. I thought of myself as the show’s unofficial director—but the truth is, Viv directs Viv. I gave moral support and what I hope was a kind, loving gaze. Sometimes that’s all it takes for something beautiful to lift off.

[Click here to explore more about Mx Bond’s work and impact.]

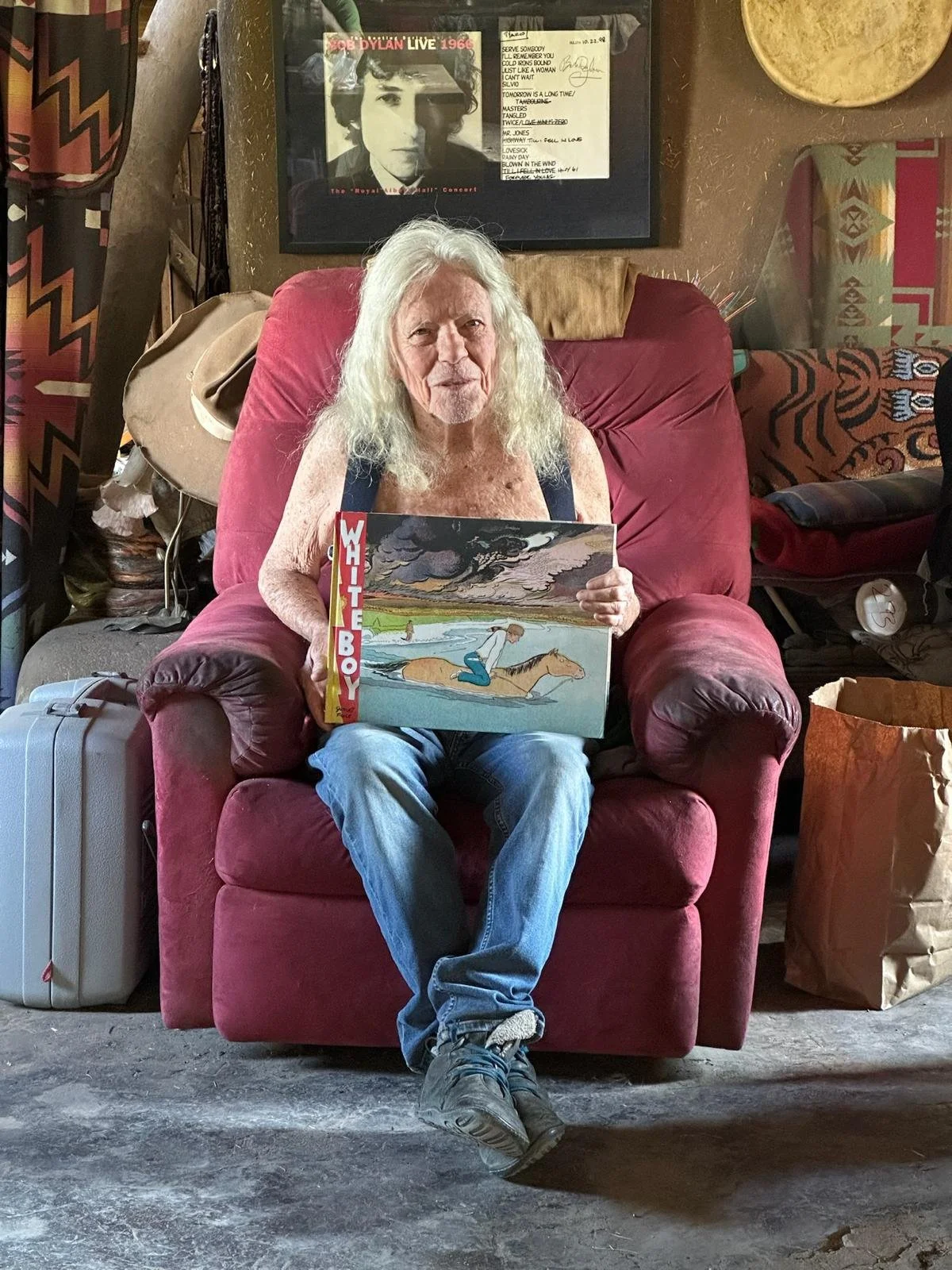

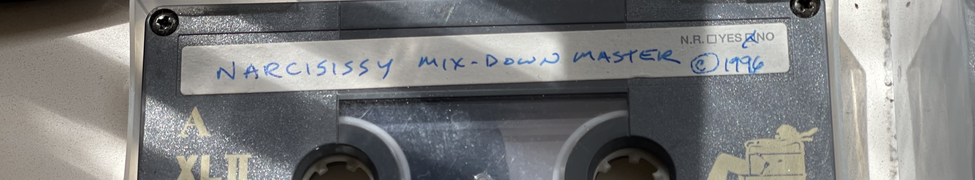

HOMAGE | NARCISISSY, SAN FRANCISCO, CA, 1995/96

Narcisissy Is 30 year old band project of Rodney Golberg and Charles Herman-Wurmfeld

When Dealing with a Narcississy

Interacting with a Narcississy requires setting boundaries and not taking our ego trips too seriously.

Don’t React: Keep your cool when faced with our grandiose claims. (We are the greatest undiscovered, banjo-based, post-punk harmony act of the mid-1990s.)

Set Boundaries: Know when to walk away from our self-absorbed performances and over-written song descriptions.

Relate Carefully: Feel free to connect with the lyrics and stories here, but don’t take them personally. All this was recorded before “PC” was a thing.

Enjoy the Show: Appreciate the theatricality, but avoid getting tangled in our drama.

Share the Obsession: Tell your friends — they deserve to know about us.

Lost in time but partially recovered, for your listening enjoyment. These songs were recorded by Mark Yee. Only half the mixtape exists and is presented here — the other half is lost. If you have Side 2, let us know!

Imagine our surprise when this half-erased mixtape turned up among the Hi8 and Super 8 films stored in the very top of the closet.

Oh, the cognitive dissonance and innocence of the 1990s. Oh, queer romance! Here are some of the songs created by Rodney and Charlie during their brief, tumultuous several months together in 1995–96.

Let’s deconstruct expectations like we did as toddlers, gleefully smashing building blocks. Let’s explore desire and disappointment while bopping along to punkish banjo stylings that could make even the most stoic operational thinker tap their foot. The cyclical nature of fleeting connections — who could keep track? Not us.

We hope our harmonies will keep you smiling while you teeter around this offering. Is it rational? Grandiose? Absurd? You tell us. Object permanence has never felt so casual or contradictory, yet here we are relating afresh. Perhaps you will too.

Here’s a slice of the 1990s echoing into your post-apocalyptic dystopian moment. Listen up!

WARNING:

this material contains graphic, sexually explicit language (& a banjo). May create inexplicable urge to return to 90’s era, queer, underground San Fransisco. Listen at your own risk. This is not music for children. Extended play may cause Banjo-sic shock syndrome.

Credits

Released April 23, 2025

All songs by Charlie and Rodney

Recorded by Mark Yee

“You Shook Me All Night Long” by AC/DC appears here while the overlords allow it.

License: All rights reserved